Theodore Roosevelt Dam

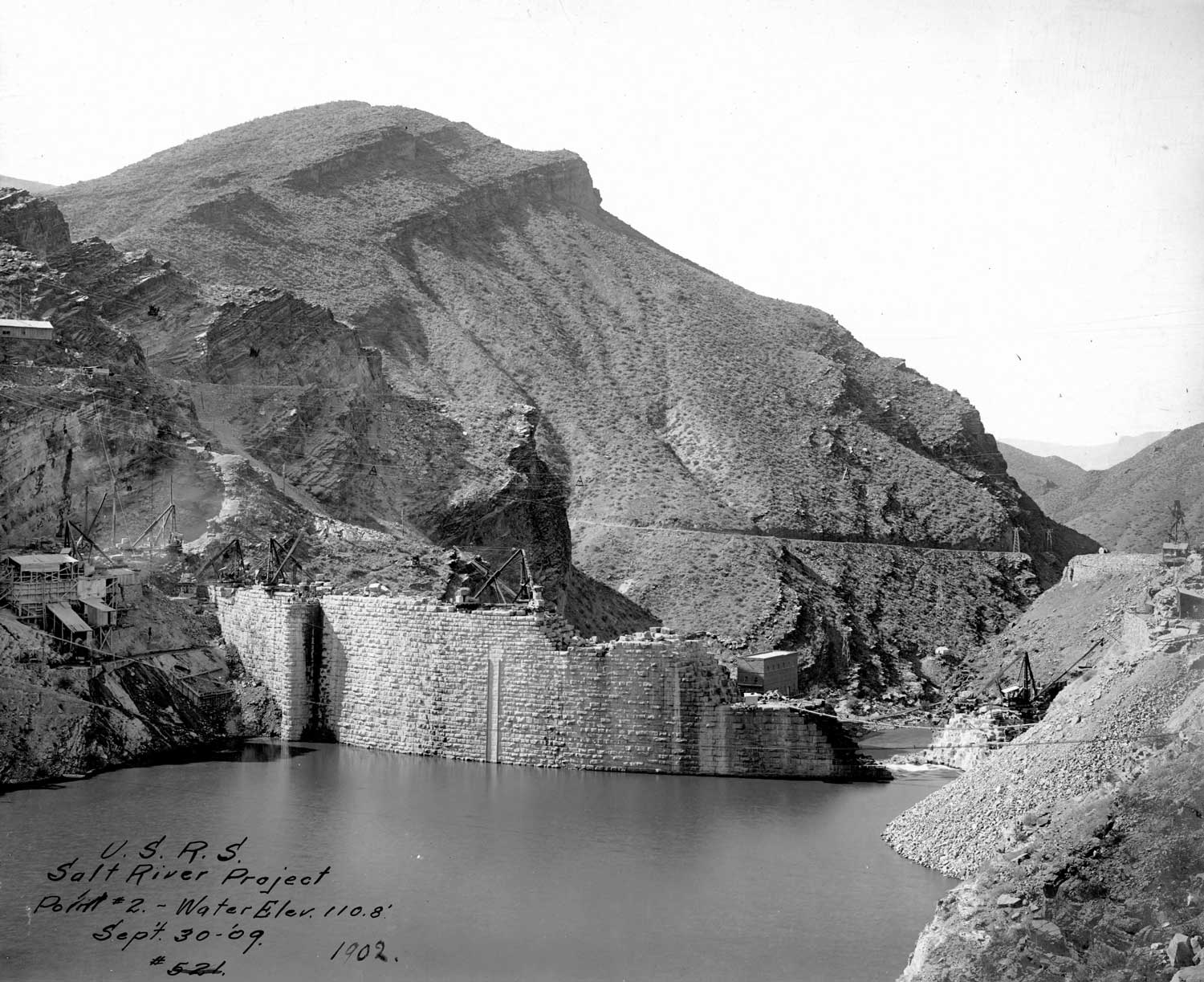

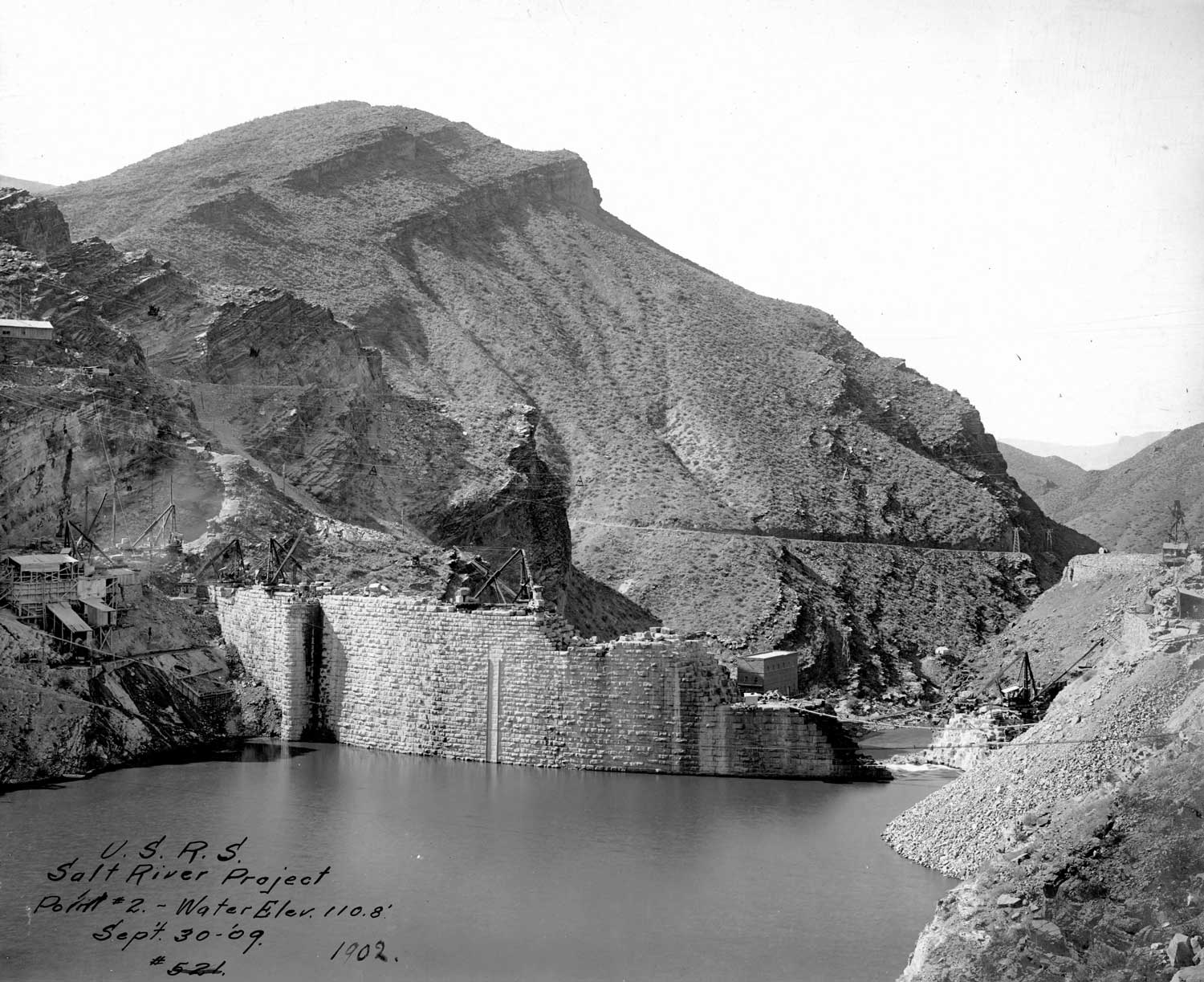

Profile; ?>Theodore Roosevelt Dam was constructed along the Salt River within the Tonto Basin region, roughly 80 miles northeast of Arizona’s capitol, Phoenix. Construction on the original rubble-masonry gravity arch dam began in 1905 and was concluded by the end of 1910. Due to its remote location in the Arizona Territory (which did not achieve statehood until after the dam was completed), a road had to be built before dam construction just to move materials between the city of Mesa and the dam site. Originally called the Mesa-Roosevelt Road or Tonto Wagon Road, it was later named the Apache Trail sometime after 1915, and was used to promote scenic tourism through the area.

Funding for the construction of the dam was possible following the passage of the US Reclamation Act of 1902, signed by President Theodore Roosevelt. The Act allowed for federal financing and construction of irrigation infrastructure, which would later be repaid by the local water users. To be selected as one of the first five reclamation projects in the US, water users in the Salt River Valley came together to form the Salt River Valley Water Users’ Association (SRVWUA) in 1903. The SRVWUA became the entity which managed the water stored behind Theodore Roosevelt Dam, and its members were assessed fees to repay the federal construction loans.

Upon completion, the dam was 280 feet tall and 1,000 feet long, making it the world’s largest stone masonry structure at the time. The reservoir covered over 17,000 acres, creating what was also the world’s largest man-made lake. The dam was modified due to increased safety standards in the late 1980s, a project which was completed in 1996. The modifications raised the dam to a height of 357 feet and also increased the storage capacity of the reservoir by 20 percent. Today, the lake covers 21,493 acres. The rubble-masonry surface of the dam was also altered and is now encased in concrete, though the original light fixtures remain prominently in place along the dam’s crest as a homage to the original structure.

Theodore Roosevelt Dam marks a turning point in the prosperity of the Salt River Valley. Although a vast network of canals had been dug in the area prior to completion of the dam, the Salt River was an unstable, unreliable source of water for the farmers in the area, prone to both drought and flooding. The reservoir and dam provided a more secure water supply in times of drought, and protection from flooding. Roughly ten years after the dam’s construction, the acreage under cultivation in the Salt River Valley nearly doubled, as did the number of farmers in the region. Today, Phoenix is one of the top five most populous metropolitan areas in the United States, a feat which would not have been possible without the foresight of reclamation era policy and planning over a century ago.

Project System and Heritage Composition

The construction of the Theodore Roosevelt Dam contributed significantly to the development of the Salt River Valley in Central Arizona. Farming and irrigation had taken place in the Salt River Valley area since roughly 600 AD, beginning with the indigenous Hohokam (Ancestral Sonoran Desert peoples), though around 1450 evidence of their irrigation usage and population declined. The first Anglo settlers arrived in the Salt River Valley in the 1860s and began revitalizing the ancient Hohokam canals as well as building new irrigation structures. Irrigation in the Valley prior to the construction of Theodore Roosevelt Dam was at the mercy of the unpredictable Salt River, however, which was prone to both flooding and drought. This made farming in the area difficult, and life in the Valley arduous.

Following the completion of Theodore Roosevelt Dam, the Salt River Valley’s water supply became much more reliable and manageable. The effect on Valley farming was not only positive but swift. In 1902, approximately 131,000 acres of land were cultivated under the “normal flow” of the Salt and Verde Rivers. By 1923 however, that number had nearly doubled with 203,350 acres under cultivation and subscribed to the Salt River Valley Water Users’ Association to receive Salt River water via the Theodore Roosevelt Dam. The number of farmers in the area also doubled, from 2,130 in 1910 to 4,359 in 1921. Today, the Reclamation Act of 1902 and the construction of Theodore Roosevelt Dam is often cited as the springboard which allowed the Phoenix metropolitan area to grow and flourish.

Without a stable water supply and the agricultural industry which came with it, Phoenix likely would not have sustained a significant population, much less become one of the top five largest metropolitan cities within the United States. In addition to its contribution to the growth and livelihood of the Salt River Valley and the Phoenix area, Theodore Roosevelt Dam also represented engineering excellence at the time it was constructed. Before dam construction could even commence, a road between the city of Mesa and the dam site had to be completed. Mesa was 60 miles away, and there was no road between the dam site and that city. A road did exist between the dam site and Globe (only 40 miles away), though it was rough and dangerous. It was determined that despite the construction costs to build a new Mesa-Roosevelt road, freighting costs to haul supplies from Mesa would be cheaper than hauling from Globe. Road construction proved difficult and hazardous, and even after the road’s completion in 1905, it was still a treacherous journey to the dam site. Therefore, engineers tried to source materials from around the construction site, including stones cut from the cliffs surrounding the dam, local sand and clay deposits for the mortar and concrete, and lumber cut from the nearby Sierra Ancha Mountains.

Construction of the dam itself was often delayed due to flooding, though the area had been plagued by drought in the years prior. The first flood occurred shortly after the excavation of the dam’s foundation, in late 1905. The foundation, which stands on bedrock, was ready by 1906. The first stone was laid in September of that year. Progress was continually slowed by the heavy flooding, which disrupted work and damaged or destroyed equipment. Labor shortages were also occasionally a problem, and workers were brought in from across the country. In addition to local workers including those from the nearby Apache tribe, newly immigrated Italian stonemasons from the East Coast were brought to Arizona to work on the dam. Mexican laborers also joined the workforce, as did many African Americans from Texas. The crews were typically small (220 reported in 1908), but the work was consistent. Electric lights were strung to allow work to carry on even into the night. The structure was considered substantially complete by the end of 1910 and was dedicated by former U.S. President and namesake Theodore Roosevelt on March 18, 1911.

The completed dam included two large spillways on each end of the structure, which could allow excess floodwaters to pass by the dam without it overtopping. Also, of structural importance was a sluicing tunnel for flushing silt out of the reservoir, which doubled as a diversion tunnel during the construction phase. Particularly innovative was the inclusion of water pipes built into the downstream face of the dam, designed to cool the surface through evaporation. These cooling pipes were added to the design following concerns that the fluctuation of temperatures in the region (particularly the extreme heat) could compromise the dam’s structural integrity.

Benefits

In 1917 the federal government transferred operation of the first project completed under the National Reclamation Act, the Salt River Project (SRP), to a group of local waters users in Arizona, the Salt River Valley Water Users’ Association (Association). The transfer marked an important milestone in the early days of the nation’s efforts to develop water infrastructure in the West. It also carried with it an understanding that would become a hallmark of future projects: that the success of reclamation projects required not only federal investment but also a strong base of local support. As the first project operated by a local entity, SRP became the model of what reclamation could accomplish in developing Western lands.

The collective spirit that guided the Association’s early development was not a certainty at its formation. When the Association was formed in 1903 as a mechanism for residents to put forward their lands as collateral for the federal funds to construct Roosevelt Dam, the idea of a common organization to unify the competing interests of Valley water users was viewed with skepticism by many who saw it as an unwarranted intrusion into private endeavors. The experience of local water interests up to that time was marked by litigation and division more than cooperative and shared purpose. In light of this background, the Association’s formation and ultimate success in unifying disparate interests is even more significant. Valley residents ultimately realized the federal support to build the necessary water infrastructure for growth could only come through local collaboration and pooling of interests that justified such a large investment. In the process, Arizona and SRP grew together into a state of several million residents and an organization that today supplies nearly 800,000 acre-feet of water annually and delivers power to more than a million customers.

The founders of the Association clearly understood that Roosevelt Dam and the irrigation and power systems it fed were the keys to the long-term growth and prosperity of the Valley. This realization, born of drought, floods and false starts, came with an understanding that the project would only be a success if it had a broad base of local support. Previous efforts to build a large storage dam failed principally due to a lack of consensus about who should bear the costs of the project and how the benefits would be distributed. The Association was founded by a coalition of commercial farmers and small ranchers; wealthy businessmen were balanced by corner grocers, "boosters" and "real farmers." No one group could ever completely capture the Salt River Project and redirect it for its own purposes. The solution to most conflicts usually required expanding the community of those with a stake in the organization rather than limiting its reach. This became a key strength of the Salt River Project—its ability to represent a broad spectrum of local stakeholders. As its home community changed, marked by a shift from agriculture to an increasingly urban service area, SRP responded to the needs of its customers by strengthening its role as a power provider.

This important facet of SRP as it is known today was not an especially important consideration at its founding. However, power quickly emerged as an indispensable tool in meeting the challenges of building the ambitious, unprecedented Roosevelt Dam. Lacking an available power supply, the dam’s engineers utilized the natural drop in elevation at the dam site to generate hydroelectricity. Before the dam was complete, the power canal generated enough surplus electricity to supply well pumps and industrial customers in the Valley, simultaneously reflecting the growth and supporting additional development in a cycle that has continued for more than a century. With the completion of additional hydroelectric dams on the Salt River, SRP embarked on a program to electrify the Valley’s farms, houses, and businesses—years before the passage of the Rural Electrification Act as part of President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal— while constructing a financial engine that could sustain water development for generations to come.

From its earliest conception, SRP was created by—and for—the communities it serves. Over time, SRP’s water and power services have helped ensure the successful achievement of its original purpose: the economic development of the Valley and the region. When Theodore Roosevelt Dam was completed in 1911, the population of Maricopa County was less than 35 thousand. On his visit to the Valley for the dedication of the massive storage dam that bore his name, President Theodore Roosevelt assessed what he saw as the bright prospects of a burgeoning community. To a crowd gathered on the steps of Old Main at Arizona State University, Roosevelt declared: “I believe as your irrigation projects are established, we will see 75 to 100 thousand people here. . . . You have the great material chance ahead.” In the 108 years since his speech, the water and power provided by SRP have helped the Valley harness Roosevelt’s “great material chance” to a degree even the president might not have imagined— today, the Phoenix metropolitan area boasts over four million residents, placing it among the largest in the United States.3 Just as it has throughout its first century, SRP continues to build upon the achievements of the past in pursuit of a better future.

Water Heritage

Engineering utility vis-à-vis designed utility

The dam continues to serve as it was designed to, operating in conjunction with the vast system of dams and canals which deliver water to the Phoenix metropolitan area. Following modifications to the dam between the late 1980s and 1996, the utility of the dam was improved to continue serving the area for generations to come. These modifications not only made the structure safer; they also increased the storage capacity of the dam by raising its height by 77 feet, providing even greater water assurance for the Salt River Project’s customers in times of drought. The spillways were also deepened to allow more water to be released during flooding incidents. A new lake tap was added as well, further increasing the amount of water which can be released from the reservoir.

HIGHLIGHTS

Country: USA

Province: Arizona

Latitude : 33.671073 N Longitude : 111.161131 W

Built: 1911

River: Salt River within the Tonto Basin

Basin: Colorado River Basin

Irrigated Area: 248,239 acres (100458.759 ha)

70th IEC Meeting, Bali, Indonesia, 2019